Edward Normalhands Process Documentation

This article is by Bucky Miller. This article is part of the CATSmas+ residency in 2023.

In 2023 the CATSmas+ residency acted as the driving behind-the-scenes force for Edward Normalhands, the tenth MoHA Holiday Show. The residents were split into two teams with specific sets of goals: Jess Bee, Emily Gilardi, and Stephanie Page handled the costumes, while Rose Ott, Celine Lassus, and Serena Zam were in charge of props and visual effects. The people at The Museum of Human Achievement, in line with the experimental tenor of the whole endeavor, thought it might be a good idea to enlist a documentarian to help chart the process for this wiki.

Overview

Within minutes of first arriving on set, the documentarian inadvertently shattered a lava lamp that was meant as set decoration. He felt terrible! The lamp went flying off a high platform near the back of the theater, where the play’s narrator would soon sit, and banged off several equipment cases before exploding against the concrete floor of MoHA’s big room. It was lucky that no bystanders were standing below.

“Oh no,” someone said.

Someone else, “what was that?”

“Lava lamp.” Turns out the psychedelic goop on the inside is just hot water and wax. Released from its vessel, the substance gives the impression of a wet candle coughed up by a cat. While sopping up the mess, the documentarian offered to replace the lamp.

“That’s very nice of you, but it is not necessary.” said someone in tie dye. This turned out to be Neil Fridd, one of the play’s organizers, “this whole thing is the embodiment of breaking a few eggs to make an omelet.” It was soon clear that Neil was correct, and in a way that was quite welcome to everyone involved.

The consensus was that working on a MoHA Holiday Show, and this one in particular, hit a rare sweet spot at the intersection of DIY and techy proficiency. Or, as Serena Zam said, “it was so good to be part of something both scrappy and professional.” Stephanie Page described the experience as punk rock theater magic.

Overall, the crew seemed to consider this duality a fundamental, generative part of the production. When interviewed, nearly every CATSmas+ resident highlighted the rapid turnaround time of the project: there were only about two and a half weeks between the moment everyone received the script and opening night. “I think the biggest challenge was the time crunch,” said Serena, “In my past theatrical experiences, we basically had months to prepare. However, the nature of the MoHA Xmas play is that it comes together in just a couple of weeks.” She saw the benefits of having to commit to things that weren’t quite perfect.

Emily Gilardi called the process a “lesson in letting go.” She said that since there was no time to second guess themselves, the crew had to go with their first thought. This worked in their favor, and allowed for the bricolage charm that not only defined the visual aesthetic of the play but matched the tone of the live production itself. (With Zac Traeger controlling the soundtrack, on one night of the play, for a second or two, the audience might have heard a couple bars from John Williams’ Phantom Menace banger “Duel of the Fates.” The next night that song may not have shown up at all. “I’ve used the Wilhelm Scream in the past,” said Traeger.) More time to plan, according to Emily, would have just meant more second guessing.

Zac and Neil, co-founders of the MoHA Holiday Show, see the spirit of the productions as something closer to a concert than to traditional theater. Said Neil, “It’s loud. It rocks. It should be the ultimate warehouse experience.” They believe in treating source material with irreverence, and often work from only a baseline memory of the original story. The fact that the hands of the makers are so visible is not only welcome, it’s a fundamental part of the ethos. To that end, Emily added, “the show is a really good example of what people in our community can do by collaborating. It shows what we’re capable of with our talent and very little money: the most beautiful set you've ever seen, built out of cardboard.”

So the broken lava lamp was swiftly replaced, a new one cemented to its nightstand pedestal so no further accidents would occur. Wise Winona would have it by her side for the entire four-night run of Edward Normalhands as she narrated the conspiratorial antics of a town where nobody could hold things but everybody was horny. It kind of makes sense. The play, in the end, was a success. Christmas was saved. But the eggs that were broken along the way may not all have been apparent to the audience.

Edward Normalhands was written by Andie Flores, Sam Mayer, Sawyer Stoltz, and Megan Tabaque (Megan also directed). Andie and Sam were CATS+ alumni, so they knew how to cater the script to the residency’s particular focus on the tech arts. This year’s residents and other crew were well equipped to make the play happen, but they still had to work on the fly. One exemplary anecdote of what sorts of problems arose came from actor and crew member Dom Rabalias: Santa’s (Sam’s) microphone stopped working, and Dom knew how to fix it, but at that moment had elves for hands. Said Stephanie, “the main characters needed access to their hands and fingers, but also needed them obscured as best as possible, and given the amount of time we had that was the biggest challenge for costumes.” Dom, who played at least three characters in the show, was not so fortunate as to have accessible fingers.

Small tweaks to some of the visual effects were made between shows, for instance an adjustment to contrast so emojis would stand out better on the monitor when imaginary droves of people were reacting to Peggy’s content. A leaf blower that was rigged to expel confetti from crotch-height continuously misbehaved, and on the first night simply ejected half of itself out toward the audience while its contents meekly spilled out at the actors’ feet.

On a similar note, much debate was had after the first night regarding the show’s climax: the thick, goopy drizzle of wet, wet “snow” that oozed out of a contraption near the 5G Tower was of such an unsettling consistency that there was little agreement on whether it was “good” or “too good.”

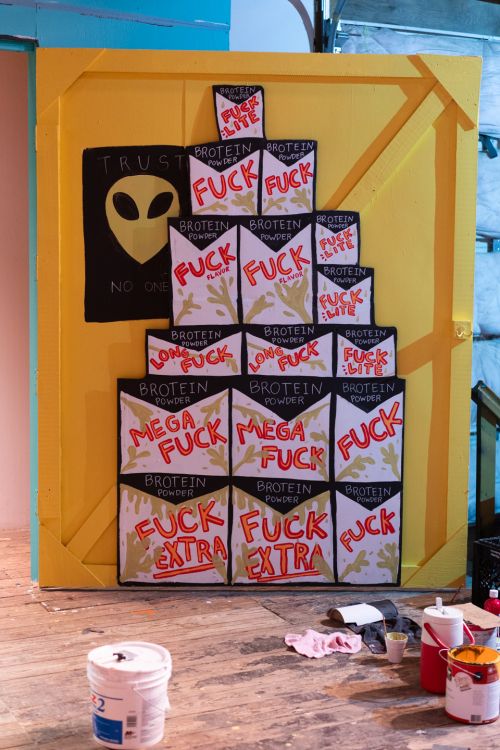

And then there were the problems that only impacted folks behind the scenes and had no bearing, or perhaps even improved, the audience experience. Maggie, one of the MoHA volunteers helping to paint the set, was responsible for making Bro Slogan’s Man Cave. She used Rose Ott’s prototype Brotein Fuck Flavor design as source material, but also had to come up with a lot of the details on her own. In her words, “I had to look up a bunch of Joe Rogan stuff on Google and it is really throwing off my algorithm.”

The laboratory-like environment extended even to the bar, donation-based, at which patrons could elect to have beers duct taped to their hands. Though the mechanics of this “cocktail” were tested, there is no clear evidence that it was ordered by anyone in attendance.

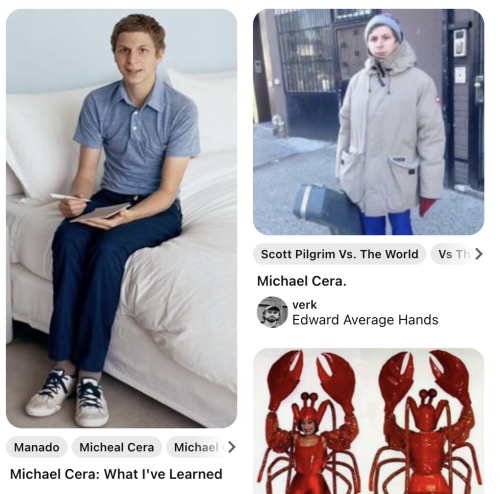

To hold all the discrete parts together and keep everyone on the same page, the crew made use of a dedicated Discord channel. The channel was used to share announcements about call times, send out requests for troubleshooting help, and in general pump each other up for the show. Discord also ended up being a tree from which other tech branches could grow. At one point, Zac shared a Pinterest board of Director Megan’s with a link that read, “23 Edward Average Hands ideas in 2023.” A small plurality of the pins on this board, narrowly edging out images from the original Edward Scissorhands, were photographs of actor Michael Cera standing or sitting upright. Residency Director Rachel Stuckey frequently used the Discord to share links to Google Docs with notes from production meetings. The last meeting in the channel is from Rachel, with information on the hot chocolate and vegetarian chili that would be available at the wrap party.

Costumes

Team Costume was composed of Jess Bee, Emily Gilardi, and Stephanie Page. This group has worked together on the past seven MoHA holiday shows, making them some of the most seasoned of the annual collaborators. Every year, Jess, Emily, and Stephanie are given some basic parameters to work with, such as the script and, this year, “hands.” It is perhaps no surprise that making outstanding hands for Edward Normalhands became priority number one. The trio of costumers were given the chance to converse with the cast and get a sense of their desires for their characters’ wardrobes. According to Stephanie, “some people have specific ideas about their look and others are very blase and open to whatever.” Beyond these limited guidelines, the look of the characters is left mostly up to Jess, Emily, and Stephanie.

Their process begins with a group trip to the Goodwill Bins (the thrift store’s pay-by-the-pound clearance outlet), which Stephanie called “a literal treasure trove.” Because there is so much freedom in the costuming choices, and such a limited amount of time, the Bins provide the team with direction. During the initial trip for Edward Normalhands, they found a plush fish tail, along with different material that matched the look of the tail and could be crafted into a head: hands! Stephanie estimated that 90% of the material used in the costuming was thrifted. If there is something very specific they needed, they would source it.

Overall, the aesthetic motivations of the play leaned heavily on the 90s/60s/70s kitsch from Edward Scissorhands. But while the original Edward is something of a goth icon, the titular character of this play, according to Stephanie, “stood out in normcore way.” Edward Normalhands’ vest and shirt were coordinating, but mismatched, all very earthtoned.

After the initial thrift binge, the three costume artists split off to work on different elements of the play while harnessing their own specific skills.

Emily spoke of the fun and freedom of MoHA productions, especially when compared to the more traditional theater jobs she’s worked. This year, she thrifted a pile of infant Christmas clothes that became outfits for four elf puppets she made. It was her first time making puppets, but they were widely celebrated by the crew. Though they were more or less quadruplets, each was able to express its own personality through its Christmas baby wardrobe. These were the same puppets that kept Dom from fixing Santa’s mic, which, due to the class war between Santa and his elves that is depicted in the play, ended up being wholly appropriate (elf solidarity forever).

Jess was the foam expert of the group, which led to creations like the internally much-beloved onion hands. Plush, sparkly, and oversized, these were essentially onion-shaped hand warmers. They were featured prominently during an early moment in the show when a member of the ensemble ran across stage screaming about the fact that, due to 5G, their hands were now onions.

Perhaps even more significant to the story were Jess’s barbell hands, which were worn onstage by Bad Podcast Boyfriend Bro Slogan. The barbells provided a little extra seasoning to Bro’s already over-the-top male fragility, and were visually distinct. At the same time they allowed Bro, a primary character, some degree of manual dexterity.

Stephanie is a self-taught sewist, but said that even more important to their role than sewing was “the ability to loosely conceptualize a character's look and then go to the store to find the ‘puzzle pieces’ to make it so.” This is, again, partly a byproduct of a compact prep time. The costumers then use their skills to dismantle, adjust, and reassemble the puzzle pieces. For example, Stephanie found Winona Ryder’s (Sabrina Ellis) dress, but it was a little small. So they used tools to remove the zipper and added grommets for a lace-up closure. This way the dress would fit Sabrina and still be available in the future for someone else to wear. Stephanie also used a hotfix tool to apply rhinestones to a bow they made for the narrator, Wise Winona (Erica Nix). The costumer’s hope was that by making this visual connection to Winona Ryder’s outfit, some people in the audience might understand the two characters were different versions of the same person. “Which is why it’s such a mindfuck that they kiss in the end,” added Stephanie, “I don't think many people did catch that.”

Further, Stephanie pointed to sewing machines as pretty magical technology. And following from there, they saw tissue paper as a helpful tool. “For the MILF Squad I was envisioning some frothy little capelets inspired by vintage lingerie,” they said, “but they needed some stage oomph and X-Mas love so I added the sparkle garland to the bottom.” But while sewing it on, the garland was getting stuck on the sewing machine foot. Stephine found that by adding a layer of tissue paper on top they could quickly sew over the garland without it catching, and then rip off the tissue paper.

When it came to hands, Stephanie made use of a lot of cardboard. It’s an easily malleable, relatively rigid material. But it isn’t so durable, so anything made this way was created in duplicate so it wouldn’t wear out over the course of the play. These included Winona Ryder’s Motorola flip phone and “actual scissoring” craft scissor hands. For the MILF Squad hands, in a pinch, they turned to dishwashing gloves. They said that they wonder where the MILF hands could have gone if they'd had more time.

-

Video credit: Stephanie Page

-

Video credit: Stephanie Page

-

Video credit: Stephanie Page

-

Video credit: Stephanie Page

In order to make efficient use of a tight schedule, and to keep track of all the costuming minutiae, Emily put together a two-tab spreadsheet in Google Sheets. This document kept track of actor measurements and detailed who was wearing what, when. The top table included columns like “HUMAN,” which listed the names of the actors, “HANDS,” describing what the humans would have over their hands, and “handedness.” Fun fact: only one of the actors was left-handed, but this reporter will not reveal who. Guess!

Lower on that page was a second table, which outlined the costume crew’s hand inventory for the first big musical number. During that song, members of the audience were brought onstage to dance behind the performers while wearing specially-made audience hands. Milk jugs, clogs, onions, and clams were reserved for the cast, the last of which motivated performer Itai Almor to sing, “my hands are clams I love my life.” Meanwhile, audience participants were assigned extremities from a list that included: drawer hands; 40 oz. hands; wrench hands; rusty pickup truck hands; slip and slide hands; dildo hands; mouth hands; dog hands; slimy fish hands; “one giant pink thumb.” In this table’s materials column, where many of the props were explained to be made of cardboard, it was pointed out that “actual milk jugs are funny.”

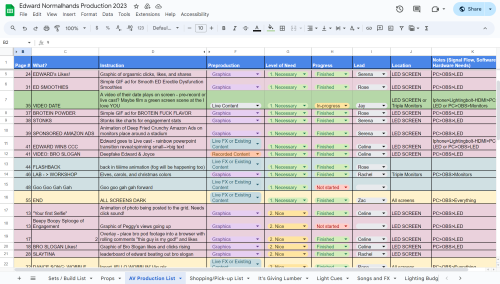

A second tab on the Google Sheet is a make/buy list. According to Emily, this common tool in theatrical costuming compiles details on who is responsible for making or sourcing certain items. This list is color-coded by actor, with the responsible costumers listed in their own column. As the name implies, other columns highlight what must be “made” or “bought” for each character in the production. Rachel Stuckey also commented on the usefulness of shared spreadsheets, a tool that “made it so easy to prioritize what had to be made and what could be made if someone had extra time, determine what elements could be reused, and delegate to a wide number of people.” Rachel pointed out that Sheets was not just useful for costumes, but helped keep props and AV elements organized as well. It especially helped with getting volunteers and drop-in residency participants involved.

Props and Visual Effects

The props and visual effects team was Rose Ott, Celine Lassus, and Serena Zam. Each of these artists brought their own sets of skills to an unpredictable assortment of tasks ranging from digital animation to on-the-fly sculpture. Rachel Stuckey, Zac Traeger, and Jay Roff-Garcia also lended their services to the AV team, training residents, running cables, troubleshooting, and coordinating various tech aspects. According to Rachel, the tech team used “a very collaborative piecemeal approach incorporating many artists, methods, and laptops.”

Serena was the primary person responsible for making and finding props for the show, and also helped with video. She used the AI-assisted note taking web app notion.so for notes and task tracking, and did crafting and prop-making research on youtube and reddit.

She made prop gelatin desserts by filling actual vintage Jell-O molds with gel candle material, a blend of 95% mineral oil and 5% powdered polymer resin that may be purchased in DIY kits. She dyed the candle substance to look like Jell-O and then used spackle for the frosting. At the conclusion of the play she brought them home, where they now adorn her living area.

Meanwhile, her car is now decorated by the small severed head of a plastic man. This is because Serena was also responsible for making the Jeff Bezos action figures that the play’s Santa would push as that year’s hot toy. She made two versions, starting with action figures of men in suits and then building oversized, bald and shiny Bezos heads on their necks. One of the figures was originally Mr. Bean, while the other was an unidentified older white man in a gray suit. Some argued it was a Dr. Fauci figurine, others claimed Sam Waterson, still others the Chair of the Federal Reserve. Nobody could agree. For the heads she used polymer clay, which was more fragile than she’d hoped but easy to build up and paint into a Bezos noggin.

“This opportunity definitely allowed me to stretch my creativity and play with materials that I have not utilized before,” said Serena, “it might be fun to use these new skills to create interesting sculptures in the future.”

Rose Ott was on the digital assets creation side of things, and was responsible for some of the animated GIFS that played on the LED wall and TV screens. She made the Broslogan Death animation, Smooth ED Ad, Back In Tiiime Gif, and Wobbly Jello Gif, and the the Brotien Fuck Flavor Ad. Her favorite was Bro’s death animation: “it is just so dumb and so fun not only in concept but in execution.”

She made the animations with the Unity engine because she feels comfortable enough in it to “dream up almost any kind of digital creation and at the very least create a rough approximation of it.” This process caused Rose to realize she could use her tools for more than they were designed for. “I was stuck trying to figure out the “right” way to do things rather than just doing things in the way I know how to,” she said, “Is Unity a proper animation tool? No. Will it help make this show possible? Yes!”

Once her graphics were complete she recorded them using ScreenToGif, a free online screen recorder tool.

Celine Lassus was active both in pre-production and during the play itself. They made graphics, gathered A/V assets from the actors, handled live-stream, VJ, and projection duties. They came into the project well-versed in After Effects and Premiere. They had also used the facial animation software CrazyTalk 8 in the past, and decided this would be a good way to create the Edward/Bro deepfake sex tape for the play. But then they found out the software had expired. So, as they put it, they “found a sketchy version online and probably fucked up my computer somehow but its so weird and goofy looking that it was lowkey worth it.”

They also used a website called MakeWordArt.com to make the Microsoft Word-style Ewdard graphic—“pop on a twirl effect in after effects and layer some confetti and I made a simple reveal that I was happy with”—and GifCities.org, a search engine that pulls gifs from GeoCities, to hunt for useful, crunchy graphics—”doom scrolling through Google just isn’t as efficient.”

VJing, meanwhile, was a relatively fresh experience for Celine. They wrote a through description of their experience learning VJ software VDMX on the job:

I was very new to VJing. Still am. But now I know some things and was able to play off that new knowledge each [subsequent] night. I feel like I didn't become a fully comfortable VJ artist until after the last show, when I was playing around with different videos and effects for the after party. Lol. It was like bootcamp. Exposure therapy. I was scared a lot of the time, because what if I fucked a cue which fucks up another aspect of the play? Working live was scary since I hadn't worked in theater in over 5 years. We keep saying it, but the culture of ‘just make the thing and whatever comes out of it is the vibe’ was so comforting to my wannabe perfectionistic brain. Grateful for Zac who would unlock a new part of VDMX every now and then. It definitely would’ve been overwhelming if I was taught all I learned at once. But in bite size ‘hey you can also do ___’ it felt feasible. I went from never having touched a MIDI controller before to making that ish my bitch <3

Sometimes I would press a button at the wrong time and yikes! Must undo! Or I would forget to press a button and oh no :( the audience didn’t get to experience the play to its fullest. But then I remember it's the first time the audience is getting to see our show and it's all magical to them. They come in with no expectations and that really comforts me.

Using the MIDI controller felt like learning an instrument. And I don't play any soooo yeah I was unlocking some new skills. The sequence of loading cues would have me pressing X then Y then X and Z then pause then X again. This was probably the most daunting aspect for me. I had my buttons labeled but it generally came down to muscle memory when working live. This was probably the most challenging aspect but also the most rewarding.

Live-streaming was integral to Celine’s VJ duties, inspired in part by writer Sam Mayer’s use of a selfie stick-mounted smartphone during the 2022 MoHA event Game Show Game Jam. Throughout Edward Normalhands, Leggy Peggy and Edward would repeatedly go live from an old iPhone that was donated to the production by former MoHA intern Devin. It was play Production Manager and MoHA Digital Arts Coordinator Jay Roff-Garcia’s job to wrangle the live cam during performances. Jay fought through the crowd nightly to relocate the phone and its tripod to various set areas, using human power to give the impact of a multi-camera set up with very little technology.

Is a livestream of a live performance, streamed to the same audience that is watching the actors stream, extra-live? Additionally streamy? This writer cannot say, and will instead turn to Rachel to explain how the crew even got the phone to send live visuals to the onstage monitors in the first place:

Initially we ran cables, thinking that would get a more reliable video feed than WiFi, but the length of the run and all of the adapters actually made it pretty glitchy. We ended up setting up a router with a closed wireless network and using Airbeam to send the signal to VDMX. It worked a little too well, so Zac built a hold button into the MIDI mixer so Celine could replicate a glitchy frozen video at choice moments during the play.

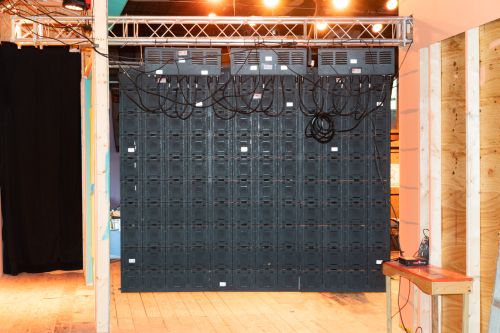

The AV crew had the strange luxury of displaying livestreams and other media on a concert-style LED wall that was donated to MoHA, assumedly not by former intern Devin. The wall was installed at stage left, near Bro Slogan’s Man Cave. It sent key moments of the play, like Rose’s Smooth ED advertisement or Celine’s potentially-computer-ruining Edward deepfake sex tape, out to the audience at a monumental scale. According to Rachel the technology for this screen is proprietary, “so it took some internet sleuthing and a weird late night video call with a strange Russian LED wall enthusiast to get it working.” Despite its strong, bright presence, each LED on the screen is one pixel. This means the resolution is only 320x384. No bother, according to Rachel, who seemed to see these limitations in keeping with the overall ethos of the production: “Making such incredibly low-res visuals,” she said, “feels satisfyingly subversive in the time of 4K streaming.”